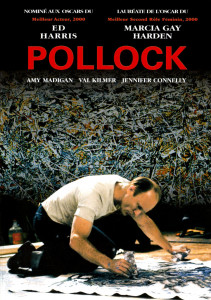

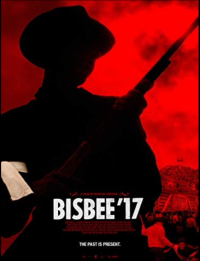

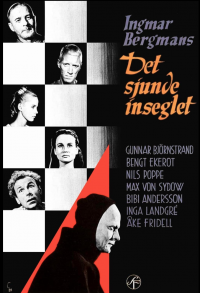

This week, Britta Gordon looks at Bisbee '17, a documentary from Robert Greene, and Jeff Godsil re-views Pollack, the painter's bio-pic, then a look at the new Criterion edition of The Incredible Shrinking Man, while Matthew of KBOO's Gremlin Time revisits Alexander Mackendrick's The Maggie (also known as High and Dry), and in the book corner, a new monograph on Ingmar Bergman's film The Seventh Seal.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––-

To return to The Seventh Seal after several decades is to discover with surprise how earthy and sometimes funny it is. The film today has the reputation of emerging from Ingmar Bergman's religious wrestlings, resulting in a somber tale of religious doubt, and indeed the film begins with bombast as ecclesiastical Dies Irae blows from the screen. Crashing waves, a rocky coast, a battle-scarred man with threadbare clothes sleeping on the pebbles, and a knight preparing to bathe in the ocean waves. Soon the character confusingly called either Death or the Devil appears and after all this time the image might be laughable, but it isn't because we are already drawn into this world, soon to be known as degraded and hardscrabble, yet still with a few opportunities for laughter and family life.

To give you an idea of Bergman's status in film you can look up an Op Ed by Jonathan Rosenbaum in the New York Times in December 2007 on the occasion of Bergman's death. He happened to die on the same day as Michelangelo Antonioni, which inspires an interesting aesthetic contrast. Rosenbaum wants to remind readers that Bergman's status was much lower than a lot of obituaries were claiming, insisting that film schools rarely taught Bergman, and that his films were hard to find on DVD, unlike his contemporaries of equal stature. The editorial created quite a stir, including five letters of rebuke to the Times itself and comments from Roger Ebert. A different version of the editorial has been posted on his website, which he says reflects more accurately his views at the time, before the editorial was rewritten and misleadingly titled.

The movie came out in 1956 and initiated phase three of Bergman’s career. He began as a screenwriter, turned to directing light and sometimes steamy generational profiles, utilizing highly attractive people, while slowly advancing to international fame with Smiles of the Summer Night, but with The Seventh Seal and then Wild Strawberries Bergman became the official go-to guy for high art cinema. During this rise, Bergman was also an increasingly successful stage director, with over 170 stage productions to his credit by the time of his death, and as Rosenbaum points out, Bergman is probably more a man of the theater than the cinema. Yet that doesn't diminish the striking images and the probing examinations of human psychology that make up his films.

The occasion for these reflections is the re-issue of Melvyn Bragg’s monograph on the film for the British Film Institute’s Film Classics series. Originally published in 1993, it is one of the best in the now 300-plus volume series.

Melvyn Bragg is a writer and broadcaster of The South Bank Show from 1978-2010 and now presents the BBC Radio 4 series In Our Time. He wrote a biography of Richard Burton, and has many award-winning novels on his resumé.

In six chapters, Mr Bragg celebrates much about the film. He begins by addressing the issue of religion and cinema, then gets personal by recounting, as many Film Classics authors do, his first viewing of Bergman films, culminating in an exclusive interview with Bergman for the South Bank Show in 1978, while Bergman was in tax exile in Germany. Here he writes about the early impact of Bergman on his life:

"Summer with Monika spoke to the condition of many adolescents in the 50s: it could have been my story or that of thousands of others. The nerve of it was that somehow and for the first time, I think, a film tapped itself into the real root of what I knew I had in some measure or would in some measure or wanted in some measure to experience. The bait was Harriet Andersson.

"She was a new type of woman. We had seen Rita Hayworth and Ava Gardner, Elizabeth Taylor and Jane Russell, the English beauties and the Mid-Western corkers. But although there were now and then certain correspondences, they were not so much brought to us on the screen as separated from us by the screen, tantalizingly behind the celluloid, creatures in a fabulous aquarium. Such sex as there was lay mainly in the land of the obvious bosoms, the twirled skirt showing the knickers or the languorous embrace. There was a top-spin in some films for those who knew, who had been there, who could pick up the clues, but it was rare for beginners to feel much more than a disturbing excitement and now and then a disappointed puzzlement.

"Harriet Andersson blew that away. She was eighteen or nineteen and looked the eighteen or nineteen of a modern late-50s girl – not the strapped and laced eighteen or nineteen of the virgin woman in embryo we were all used to on the Big Screen. Harriet Andersson could have stepped out of the screen and into the streets of Wigton any day. She would have attracted a lot of (then) polite vulgar attention, but she would not have been too far ahead of the erotic teasing to be seen in buttoned cardigans and complicit smiles in and around a town where slowly the ice of publicly policed and often privately suppressed sex was beginning to break. Harriet Andersson could have been the sexy girl at the school any number of us went to. It was she who drew me in – from photographs modestly displayed outside the Scala Cinema in Walton Street in Oxford. Once in, her mores and her attitudes struck chord on chord and here, in what was the first homesick term at a university whose codes were often haughty and tedious, speaking in a foreign tongue which we thought it a good joke to describe as English dragged backwards, was a film which made a direct impact on all the senses that cried out to be recognized as being of their time.

"Harriet Andersson’s erotic charm, her playfulness and sense of life – subsumed in her great acting talent – struck with the shock of recognition. The last sequence made me hate her and lust after her in equal and unbearable conflict.

"Though it was mostly the performance of Harriet Andersson which called me into Bergman’s world, there was more. The landscape, for instance, was not unlike the northern landscape I knew, the quality of the light, the sense of space and the possibility of solitude, the vast, grey sky, the occasional release of a short summer. More than that, though, was a seriousness of intention which I absorbed, registered in some shelf of the brain, but did not take out to examine until much later. Bergman has a deep seriousness about intense emotional relationships which I find sympathetic and with which I find it easy to identify. More than that, I consider it to be the most honest and truthful way to take on life – despite the proximity of seriousness to earnestness, pomposity and boringness and even despite the unease many feel with the fullest weight of expression of an emotion. In Bergman, people are mostly very serious about what he thinks to be serious matters: Love, Death, Religion, Art. Indeed it is his resolute preoccupation with serious concerns – even in his few comedies – that mark him out and perhaps account for his having rather fallen out of fashion recently. The seriousness and the insistence on taking on the whole of life, not a slice or a bite, the circumference of existence and what is above it, has been his chief matter, and this, together with the religious pulse, makes him somewhat alien to a post-modern and largely disbelieving world."

Next he tracks the script, which began as a play written as an exercise for his acting students. Here he notes also the influence of radio on Bergman’s approach to his work. Following this, he explores briefly the influence of Bergman's childhood experiences on his politics and theology. Next, Bergman’s summer-time filmmaking process is explored with an emphasis on The Seventh Seal, his 17th movie at the time. Finally Mr. Bragg addresses the film itself, starting with those clouds and the sea, the shot of the seemingly-static seagull, the shock cut to Death, and the chessboard. He offers a fine moment-by-moment analysis of the film, but here they we stumble upon the book’s only flaw, which is that his analysis ends rather abruptly, with the scene of the traveling actors on stage interrupted by the Plague-fighting Penitents as they march through the village. Suddenly there is a wrapping up, but the reader has the impression that Melvin Bragg simply ran out of pages in the rather confined format of the BFI series. It would've been great if the BFI had asked him to finish the book, by either restoring deleted pages or simply completing his analysis. Thus, this is not a second edition, but a reprint of the first one with a new cover. Still it stands as one of the best monographs in the series, about one of the 50 most important films in cinema history.

- KBOO