About 28 years ago, the British Film Institute decided to create companion monographs to the then 360 films the institution had chosen for permanent restoration and exhibition on a rotating basis. The first volume was The Wizard of Oz, written by Salman Rushdie. Now, 306 volumes later, the series is as strong as ever. Over the next few weeks I’m going to discuss three new volumes in the series for this year, and several new second editions.

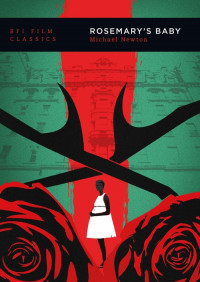

Michael Newton’s lavishly illustrated volume on Rosemary’s Baby. Roman Polanski’s masterpiece from that tempestuous year, 1968, is one of the best in the whole series. Mr. Newon is lecturer in English in the Netherlands, and has two previous books, one of feral children and another on conspiracies, and did the earlier BFI classic Kind Heart and Coronets.

Here he follows the general pattern of the series, a “making of” section, followed by an analysis, and finally an account of the film’s reception and legacy. He comes up with some production tidbits that I hadn’t know, such as that Robert Redford was the first choice for the husband Guy, eventually played by the difficult John Cassavettes (with Jane Fonda a possible candidate for Rosemary), that the voice for a phone conversation between Rosemary and the actor whose sudden attack of blindness gave guy a break in a part was provided by an uncredited Tony Curtis, and that Polanski himself shot the famous dive by Rosemary across Fifth Avenue, using a hand held camera because body else wanted to try it. That shot took five takes.

The long middle section of the book is intriguing. He claims for RB the roles of prime paranoia film, anticipating (after the earlier The Manchurian Candidate) The Parallax View and The Conversation. This makes sense. His lengthy discussion about conspiracies in political discourse is especially timely. He also catalogs RB as a great film about the tensions of marriage, which it is. And he charts the film’s cunning use of imagery of water, food, and babies, reminding the reader that both Rosemary’s Baby and 2001 that same year both conclude on the importance of a baby. I had forgotten that there are three key and eerie dream sequences. Upon re-seeing it I was struck by the superb visual craftsmanship, the clever camera placement, the in-jokes, and how much it fits in with Polanski’s “apartment” movies. Based on Ira Levin’s bestseller, it is also one of the most perfectly plotted movies ever made, and unusually faithful to the book.

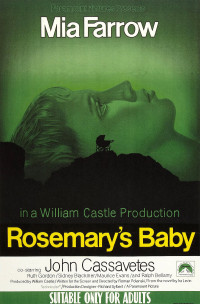

Fortunately there is a Criterion Collection version of the now 52-year-old-film, No. 630, with a restored digital transfer, a new documentary featuring interviews with Polanski, actress Mia Farrow, and producer Robert Evans, a 1997 interview with the late Ira Levin, Komeda, Komeda, a feature- length documentary on the life and work of jazz musician and composer Krzysztof Komeda, who wrote the score for Rosemary’s Baby, and a booklet with among other thing, Levin’s drawing of the apartment’s floor plan for use in plotting the novel. As does the Criterion Collection, the BFI series supplies cover art that reveals nuances about the film that can constitute new movie poster art.

As Michael Newton points out, few associated with the production seemed o be all that interested in what witches actually do, and what they believe (exceptions were the art director and the costumer). Levin was anti-religion, and Polanski found the film “fun,” and an opportunity to explore further his bent toward surrealism, his most profound influence. This quasi-neglect leads to an interesting plot hole, that he explores on page 97: If, as it turns out, Satan can be summoned to earth via a right and can take physical form, what does he need Rosemary, and for her to prove him a child? His exploration of this conundrum provides for fascinating reading. It makes the speculative reader wonder if Levin could have even gone further and posited a Da Vici Code style conspiracy, in which it was Satan himself who impregnated Mary, thus making Jesus in “reality” the son of the Devil rather than the Deity.

The question remains, though, why would we want to watch a horror film with a grim theme made by a guy with a lot of almost insurmountable baggage. Another similar film helps clarify. One can’t expect one 136-page monograph to include everything for the history of cinema and witchcraft (such as Hexan), but the reader should know that there is a surprisingly similar early precursor to Rosemary, from 1943, The Seventh Victim, Mark Robson-Val Lewton-DeWitt Bodeen-Charles O’Neal’s noir-horror film about a woman searching for her sister in Manhattan, learning that she has been consumed by a coven of witches and warlocks [A note of confusion: don’t both Levin and Polanski intend to mean that Rosemary’s neighbors are satan worshipers? Throughout the film via references and book titles, they are classified as witches, as they are in Mr. Newton’s volume.] Both films present women beaten down by the cult, and a doctor who is much more than just a facilitator, the theme of “apartments,” and the mask a city wears to disguise malice.

Aside from the usual elements that attract casual viewers to a work, both films offer such elements as good scares, a well told tale, superb craftsmanship, and with Rosemay’s Baby, there is the fact that the film says things about life from an unusual perspective, born of Polanski’s past and Levin’s take on religion in general. And as one of the great “marriage” movies, Rosemary’s Baby, in its mis-directive manner, tells us something true about what life is like.