This week, we get Jeff Godsil's take on Ken Russell's The Music Lovers, and Matthew of KBOO's monthly story dramatizing Gremlin Time on Enola Holmes 2, while in the book corner, a new BFI monograph on Ozu's Tokyo Story.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––-

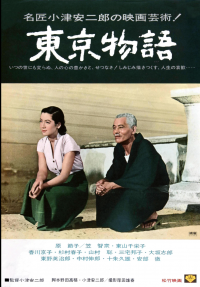

I can ’t figure out whether it is easy or difficult to imagine how western viewers might have taken to Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story (AKA Tokyo Monogatari) if they happened to see if in 1953, an unlikely opportunity. Perhaps bafflement and boredom that “nothing happens,” or being unnerved that often the characters seem to be talking directly to the camera.

On the other hand, many western writers on film have been fascinated with Ozu’s work including Donald Richie, who write the first book in English on the director, Robin Wood, who wrote on Tokyo Story as early as 1964, while David Bordwell, Joan Mellen, and Noel Burch, have all written interestingly and insightfully on the films. Most recently there was Adam Mars-Jones and his short book Noriko’s Smile.

Noriko the character is in Tokyo Story as she was in two previous Ozu films, Late Spring, and Early Summer, always played by Setsuko Haru, though in each case the characters are different people. Wood wrote of this series that “the trilogy is unified by its underlying progressive movement, a progression from the unqualified tragedy of Late Spring through the ambiguous "happy ending” of Early Summer to the authentic and fully earned note of bleak and tentative hope at the end of Tokyo Story.” Here, it’s difficult to say that she is the main character, as the tale’s attention seems to be equally divided among several members of the film’s family. But she is certainly the heart and soul of the film.

Noriko is the daughter-in-law of an elderly middle class couple who live in Onomichi, in western Japan near Hiroshima. She’s a widow, as their son died in the war. They also have a young daughter who lives at home and teaches school. As the film opens, the couple is preparing to visit their other children, two in Tokyo, one a doctor, the other a beautician, and one in Osaka, who works for a railroad. Their trip will last 10 days, one of them spent at a hot springs that the two Tokyo offspring fob them off to. The children aren’t especially prepared for their parents, and the couple’s grandchildren are awful. Only Noriko feels responsible, taking them sight-seeing, and allowing the mother to spend the night in her crowded worker’s flat. They decide to go home, but ill-heath catches up with the couple, and the film’s third quarter is occupied by one of cinema’s longest death scenes. This phase concludes with two remarkable conversations, one between Noriko and the youngest daughter, Kyoko, and one with the father, Shūkichi, played by another Ozu regular Chishū Ryū. Many such as Wood have pointed out that these conversations are what the whole carefully calibrated film has been building to.

For some reason, author Alastair Phillips talks only about one of them in his new BFI book about the nearly 70-year-old film. Alastair Phillips is Professor of Film Studies at the University of Warwick, an epicenter for close readings of films, and has previously written a Rififi film study, and edited Japanese Cinema: Texts and Contexts and A Companion to Jean Renoir. Aside from skipping one of those two conversations, this is a thorough account of Tokyo Story.

He begins with a general appraisal of Ozu and the film, background on the film’s making and Ozu’s film practice, Tokyo, Onomichi and other locations as places where characters interact, the film’s reception and current status, and in an afterword, the author writes of his own trip to Onomichi, retracing the steps of Tokyo Story’s creation. This is an excellent introduction to the film and serves as something of a template for any successful BFI classics volume, especially in its wealth of insights.

For example, he debunks the notion that Tokyo Story is an unofficial remake of Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow, writing:

“Numerous writers have pointed out the similarities between Tokyo Story and Leo McCarey’s moving 1937 feature film, Make Way for Tomorrow, which tells the story of an elderly couple forced to move out of their home because of financial difficulties and then finally separate from each other because none of their five children will take them in. [Screenwriter] Noda had seen the film on its Japanese release, but Ozu hadn’t as he was stationed at the time in China on military service. Tokyo Story is by no means, however, a direct remake of this previous template, and Noda and Ozu were more characteristically inclined to recycle motifs from previous material of their own, such as the reshuffling of familial relationships in Toda-ke no kyoˉdai/The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941) and the emblem of the visiting father in Dreams of Youth or aging father in Chichi ariki/ There Was a Father (1942).”

He also notes that:

“[Screenwriter] Noda’s original intention had been to depict the intergenerational selfishness inherent in family life, with Ozu similarly interested in the degree of antipathy that children may end up feeling for the character and lifestyle of their parents. All of this remains present in the film.”

But there are significant nuances. He continues:

“[Friend} Yoshida has famously recounted how Ozu’s final words to him before dying were that ‘cinema is drama, not accident’, and we may briefly consider this aphorism in the light of three predominant characteristics within the narrative organisation of the script: the absence, in fact, of any significant dramatic catalyst in terms of story progression and the emphasis instead on mundane but carefully plotted and revealing human interaction; the importance of dramatic parallelism (something originally noted by Donald Richie) whereby certain key events or personal circumstances are ‘echoed or inverted elsewhere’; and the intriguing, but prominent, use of ellipses at certain points within the otherwise linear progression of the plot. These aspects point to a subtle orchestration of internal elements that ply an emphatic dramatic structure with the implied effect of contingency. As Ozu himself put it, when reflecting on his narrative method, ‘Rather than tell a superficial story, I wanted to go deeper, to show the ever-changing uncertainties of life. So instead of constantly pushing dramatic action to the fore, I left empty spaces, so viewers could have a pleasant aftertaste to savour.’

As for Ozu’s distinctive visual style, he adds that:

“Ozu’s interest in dynamic spatial composition also served the function of looking ‘at people from every possible social point of view [to the extent of] incorporating various objects that were close to us’. For both cinematographer and director, this intensified scrutiny had a set of democratising outcomes linked to both a desire to project the roundedness of a three-dimensional character onto the flatness of the cinematic screen, and an awareness of the multiple ways one might therefore observe the motivations and consequences of intimate human interaction. In this sense, proximity did not just mean the matter of observing how different adult family members conversed with one another while, at the same time, being unfamiliar with the realities of each other’s lives. It also concerned the all-important relationship between the imagined family members and the imaginary spectator in the audience. As cinematographer Atsuta put it: ‘Ozu was trying to give the face a sense of three-dimensional presence, to create a relatively realistic feeling, thereby causing the audience to feel that the actors were actually talking to them.’

As a writer of a complete account of the film within a length limiting format, the author is still able to be sensitive to the historical context. He writes:

“Tokyo Story is the first original screenplay that Ozu and Noda had developed since the end of the US Occupation of Japan on 28 April 1952. The film therefore provided a timely opportunity to evaluate recent changes to the Japanese family system with five years having almost elapsed since the enactment of key revisions to Japan’s Civil Code in 1948. These amendments had enabled firmer legal equality within the institution of domestic marriage. They also accorded a greater degree of freedom to the individual rights of family members outside the traditional patriarchal security of the family home. By 1953, Japan’s material prosperity was beginning to improve, with the development of new economic opportunities in the major urban conurbations of the Kansai and Kantoˉ regions, home respectively to the two cities of Osaka and Tokyo that feature in the film. These social and economic changes had profound repercussions for how ordinary Japanese people internalised the progressive narrative of material and ethical regeneration offered by the legacy of the Occupation. On the one hand, the postwar period had encouraged a sense of economic opportunity and increased investment in the active participation of nation-building; but on the other, it had also problematised the relationship with the recent past, especially when articulated through a lingering affiliation between the traditional family system and private memories of the militarist experiment that had led to the country’s defeat in World War II.”

As I mentioned, the book concludes with a moving account of his real life experience of Japan and the film’s locations. It’s a powerful conclusion to a book about a beautiful film.

- KBOO