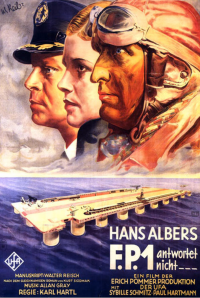

This week we discuss the new Steven Spielberg version of West Side Story, with actor and coach Kurt Conroyd, while Jeff Godsil considers Brigitte Bardot in ... And God Created Woman, then Matthew of KBOO's Gremlin Time on F.P. 1 Doesn't Answer, features Conrad Veidt as the heroic lead in one of the final films from the Weimar Republic, and finally the new Criterion edition of The Incredible Shrinking Man.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––

From time to time the Criterion Collection likes to throw into the mix a cult film or two, movies that entertained the adult high art collector when they were in their pre-teens, in essence a showing by the company of the full range of cinema’s hold over viewers.

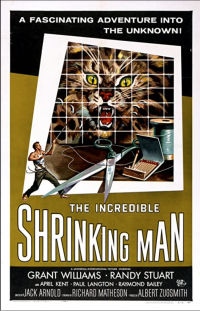

Now joining The Fiend Without a Face, The War of the Worlds, and The Blob, is The Incredible Shrinking Man.

Last week we discussed Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal released in the United States in 1957, the same year that the Incredible Shrinking Man hit the screens.

1957 is notable for other events. For example, it's the year of The Bridge Over the River Kwai; it's the year that Rock Hudson, John Wayne, Pat Boone, and Elvis Presley were the top four money making movie stars. Jerry Lewis appeared in his first film without Dean Martin, it's the year that Humphrey Bogart, Max Ophuls, Eric von Stroheim, and James Whale all died, while it was the year that Alain Delon, Catherine Deneuve, Lee Remick, and Harry Dean Stanton all made their first films. Mad, no longer a comic book but a magazine, started running film parodies.

And existential humanism was at its peak thanks to the films of Bergman and Kurosawa. Funny, then, to find this strain of philosophical self-questioning to trickling down to director Jack Arnold, and screenwriter Richard Matheson, who collaborated on the low-budget Incredible Shrinking Man.

As in something out of an EC horror or science-fiction comic, a man named Scott Carrey is out boating with his wife when he is enveloped by a strange cloud that passes by. Half a year later, he begins to notice that his clothes no longer fit, and a battery of tests revealed that he is shrinking. After a failed experiment to stop the shrinkage, he continues to become smaller, eventually living in a doll house. The second half of the movie takes place mostly in a basement, where he has been chased by the house cat, while his wife comes to believe that the cat has killed Scott. Within the basement he searches for a way out but also for water and food, while warding off a terrifying spider. His escape from the basement comes only when he has shrunk enough to pass through a grid in the house’s foundation.

Here follows the scene that sets the Incredible Shrinking Man apart not only from other science-fiction films of the time, but from every other release from that year and beyond. Realizing that he will continue to contract until he is microscopic, Scott contemplates the similarity between the vast universe and the equally vast microcosmos beneath him, point also made poignantly in the Charles and Ray Eames film Powers of Ten, made in 1977.

There is also a religious quality to the narration over the sequence, which some close readers should find typical of Richard Matheson throughout his horror and science fiction books.

This Criterion pressing, number 1,100, comes with an unusually high number of extras.

They kick off with an audio commentary track by horror and sci-fi cult film specialist Tom Weaver, who guides us through the film by telling us the background of the various stars and supporting cast and stages excerpts from interviews he has conducted with most of them. He was an unusual choice to shepherd the film, as he at times calls it preposterous, and notes that Steve Allen and another guest on his old radio show proclaimed it the funniest film they had seen in years. In short, he doesn't seem to like the movie too much, but he enjoys conversing with various mostly forgotten performers. His audio track is given over for 12 minutes by David Schechter, a specialist in movie music, who summarizes the highly complicated background of the film’s score, credited to five or more people.

There are also several short video features, including the special effects helmers, despite Tom Weaver calling the special effects in general "crummy", a section about the lost music of the film also by Schechter, a feature documentary about Jack Arnold and his years with Universal Studios, a 1983 interview with Arnold, an interview with Richard Matheson's son, who gives background on how Matheson came to write the novel, two 8mm versions of the film made in 1969 for home viewing, a sort of Reader’s Digest account of the movies, the trailer and teaser for the film narrated by Orson Welles, and in the box a booklet with an essay by Geoffrey O'Brien that is well written and informative. My favorite supplement, however, is a conversation between director Joe Dante and a comedian he is paired up with for some reason. Dante is always interesting on the outer reaches of cinema, and as a kid he toiled in the realm of fan magazines such as Castle of Frankenstein where his by-line could be found reviewing movies as a teenager. As an adult filmmaker he casts in his films some of his favorites from the grind house era such as William Schallert, who plays a doctor in Arnold’s film, but is famous for being Patty Duke's dad in the TV series.

I suppose that most people will find the film preposterous and funny, like Steve Allen, but for those with a Joe Dante level of sympathy for films that have ideas despite the poverty of their creation, this new disc is a treat.

- KBOO