Hosted by:

Produced by:

KBOO

Program::

Air date:

Mon, 02/27/2017 - 9:00am to 10:00am

More Images:

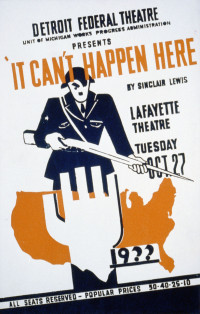

Frann Michel discusses Sinclair Lewis's 1935 novel of American fascism, It Can't Happen Here, the similarities between its fictional demagogue and our current president, the capitalist roots of fascism, and some differences of political landscape then and now.

It's the #1 bestselling work in the "classic American literature" category on Amazon dot com—though it's also available for free through Project Gutenberg Australia or the Multnomah County Library. Salon dot com called it "the novel that foreshadowed Donald Trump's authoritarian appeal."

It Can't Happen Here was written in 1935 by Sinclair Lewis, who in 1930 had become the first U.S. author to win the Nobel Prize for literature. Lewis was known for his 1920s novels like Babbitt and Main Street, which lovingly excoriated the vacuity of middle-class, middle-American, small-town Rotarians.

Although it's not considered his best book, It Can't Happen Here became Lewis's best-selling novel, and when he turned it into a play the next year it was widely performed in multiple languages. More recently, the novel has gained renewed attention, becoming an online bestseller, and the topic of frequent commentaries.

The satirical narrative features a demagogic presidential candidate who wins support among economically distressed voters with mesmerizing speeches full of anti-elitist populism; racist, sexist, anti-Semitic nationalism; inconsistent proposals; and authoritarian promises to "make America a proud, rich land again." He's published a ghostwritten book combining boastful autobiography and contradictory policy, and he slams the press as a bunch of liars.

So, you can see why it might be of interest.

But the crass and charismatic Berzelius Windrip—known as Buzz—is of course not the result of any clairvoyance on Lewis's part, but a riff on the dictators of his day. Lewis was married to the journalist Dorothy Thompson, who interviewed both Hitler and Huey Long in the early 1930s, and whose work may have provided both impetus and material for Lewis's novel.

Huey Long, in particular, provided a model for Buzz. The Louisiana Democrat had been compared to Hitler, Mussolini, and Franco, and intended to challenge Franklin Roosevelt for the 1936 nomination. Instead, Long was shot to death a month before Lewis's novel appeared, and its explicit references to him were quickly revised into the past tense.

Pundits on the political right have snarked about the comparisons of Buzz Windrip to Donald Trump, because not only is Windrip a Democrat, but also his platform, among its various and often conflicting items, proposes economic redistribution, limits to the size of individual fortunes, caps on dividends, and five thousand dollars per year to be given to every family. But it's worth noticing that in fact, this is not what he does once he's elected. Instead, Windrip's capitalist supporters were well aware of the loopholes and qualifiers in his platform, and generally find themselves much more satisfied than his working-class supporters. Buzz promotes and protects big business, bans strikes and labor unions, and, aside from thus heightening exploitation and adding new layers of graft and corruption, he mostly enables economic business as usual.

Windrip does follow through on the one item in his fifteen-point plan that he has presented from the start as most important: the consolidation of power in the executive branch. When Congress refuses to approve his demand for complete control of legislation and suspension of any interference from the judiciary, Windrip declares martial law, and has troublesome congressmen arrested for "inciting to riot." His edicts are enforced by an informal citizen militia he has regularized, known as the Minute Men, or the MMs. Within the first year, he has terminated all the older political parties and replaced them with just one, the American Corporate State and Patriotic Party, whose members are widely known as the Corpos. Soon there are concentration camps, filling with a lengthening list of dissidents, including "such congenital traitors and bellyachers as Jewish doctors, Jewish musicians, Negro journalists, socialistic college professors" and so on. The racist and anti-Semitic planks in Windrip's platform are, like his insistence on centralized executive power, also "vigorously respected," in their case because "Every man is a king so long as he has someone to look down on."

"Every Man a King" was a motto of Huey Long's, the title of his autobiography and his theme song. Unlike Buzz Windrip, Long seems to have followed through on some of his populist promises, taking on the Standard oil trust, and expanding hospitals, schools, roads, and bridges in public works programs across Louisiana. Though his methods were autocratic and his power exercised through patronage, his campaigns helped push FDR's New Deal further to the left.

But the mainstream in the 1930s was already further left than it is today. Windrip's redistributive platform reflects a widespread consensus, and explicitly references Huey Long's Share the Wealth program, FDR's New Deal, Upton Sinclair's End Poverty in California, and Townsend's social security plans, among others.

When opposition to the Corpo state gets organized under the leadership of the Republican former candidate, he declines contributions to the cause from an oil tycoon and tells him that, whatever happens,

you and your kind of clever pirates are finished. Whatever happens, whatever details of a new system of government may be decided on, whether we call it a 'Cooperative Commonwealth' or 'State Socialism' or 'Communism' or 'Revived Traditional Democracy,' there's got to be a new feeling—that government is not a game for a few smart, resolute athletes like you . . . but a universal partnership, in which the State must own all resources so large that they affect all members of the State....

It does take a while for that opposition to get organized, because, as the title suggests, so many people believe the US immune to fascist tyranny.

The main center of consciousness in It Can't Happen Here is the newspaper editor Doremus Jessup, who recognizes himself as a "small-town bourgeois Intellectual," a "rather indolent and somewhat sentimental Liberal." He prides himself on his broadminded detachment, right up until he's taken to jail for his own protection, after he publishes an editorial critical of President Windrip. Then he thinks the "tyranny of this dictatorship" is the fault of "all the conscientious, respectable, lazy-minded Doremus Jessups who have let the demagogues wriggle in, without fierce enough protest." Thus the novel criticizes Jessup's indolent complacency, and the narrative trajectory requires his rebellion.

But despite acknowledging Jessup's flaws, the book aligns us sympathetically with his perspective, and seems to share his resolute anti-Communism, despite its critiques of the capitalist inequality that can generate support for fascism. To some extent it also shares some of his other limits of vision. African-American and Jewish characters are few and relatively minor, and the only apparently queer character is Windrip's behind-the-scenes policy-and-propaganda chief, his Steve Bannon figure, if you will.

More useful, perhaps, are the observations of the Communist character Karl Pascal, who points out that grinding poverty existed in the U.S. in the supposedly prosperous times before the Depression, and that "Buzz isn't important—it's the sickness that made us throw him up that we've got to attend to."

Of course the novel is neither a prophecy nor a blueprint, but a satire and a warning, and it remains worth reading for the provocations offered by its funhouse-looking-glass reflections of American history, economy, and culture.

- KBOO

Update Required

To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your

Flash plugin.