Today we take a look at no less than three recent Criterion Collection films, Hirokazu Kore-eda's 1998 After Life, Douglas Sirk's Written on the Wind, with Rock Hudson and Dorothy Malone, and The Celebration, Thomas Vintenberg's quasi-dogme epic, each one a variation on family trouble's, while Jeff Godsil takes on the first Mission Impossible film. Matthew of KBOO's Gremlin Time comments on Francois Truffaut's The Soft Skin, and in the book corner, two new biographies of Buster Keaton.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

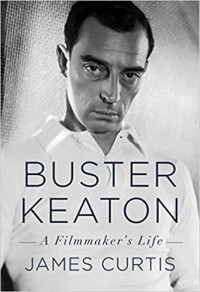

Finally we take a look at two new biographies on silent era comedian Buster Keaton, Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life, by James Curtis, from Knopf, and Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century, by Dana Stevens, from Atria Books.

Sometimes by happy coincidence two books come out on the exact same subject. This has happened again recently with new biographies of silent comedian and director Buster Keaton. Given that these projects are planned well in advance, the coincidence must be due to an anniversary of some kind, and indeed in 1922 Keaton made Cops, one of his most famous shorts. Here is what Andrew Sarris wrote about Keaton in his landmark The American Cinema, in which he placed Keaton in the pantheon and contrasted him Charles Chaplin.

“The difference between Keaton and Chaplin is the difference between poise and poetry, between the aristocrat and the tramp, between adaptability and dislocation, between the function of things and the meaning of things, between eccentricity and mysticism, between man as machine and man as angel, between the girl as a convention and the girl as an ideal, between the centripetal and the centrifugal tendencies of slapstick. Keaton is now generally acknowledged as the superior director and inventor of visual forms. There are those who would go further and claim Keaton as pure cinema as opposed to Chaplin’s essentially theatrical cinema. Keaton’s cerebral tradition of comedy was continued by Rene Clair and Jacque Tati, but Keaton the actor, like Chaplin the actor, has proved to be inimitable. Ultimately, Keaton and Chaplin complement each other all the way down the line to that memorably ghostly moment in Limelight when they share the same tawdry dressing room as they prepare to face their lost audience.”

Contrasting two entities is a great way to bring out the nuances between them. Thus in these two books, Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life, by James Curtis, from Knopf, and Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century, by Dana Stevens, from Atria Books, we have a fine contrast between approaches to cinematic figures. James Curtis is the author of books on are WC Fields, Spencer Tracy, Mort Saul and modern comedy, but is most famous for his books on directors James Whale, of Frankenstein fame, and Preston Sturges, who made five comedy masterpieces in a row for Paramount. His is the more straightforward or classical biography, following Keaton from birth through achievements to death, using as a skeleton vignettes from the making of a film by the National Film Board of Canada to promote travel there, called The Railrodder, and released in 1965, one year before Keaton's death. These vignettes offer a rare look of Keaton behind the scenes, wrestling with gags, and working with other directors. Incidentally this 20 minute short is easily available on YouTube

Dana Stevens is the movie reviewer for the online magazine Salon, and her approach is much more intimate, marbling her portrayal of Keaton with personal history, but also with attempts to place Keaton in his times, as his life parallels the rise of cinema itself. This brief quote from her book gives the flavor of that aspect of the enterprise:

“An unkillable legend maintains that the Lumières’ short film of a steam train pulling into La Ciotat station (which was first shown not at this December 1895 screening but at one early the next year) caused some first-time film viewers to run from the theater in fright, as if the filmed train were about to plow through the surface of the screen. This myth has been disproven many times by film scholars—there’s no contemporary account that mentions anything like such a stampede—but it’s easy to understand the reason for the persistence of the La Ciotat myth. If the comical image of fleeing filmgoers confused by the distinction between movies and life overstates the visual naiveté of cinema’s earliest viewers, it does accurately register the symbolic violence of the rupture moving pictures were about to make in the fabric of the wider culture. They came at us with the speed and force of a moving train, and after the (pleasurable) trauma of that first filmed arrival, the distinction between the filmed world and our own would never quite be reliable again.”

Here is Ms. Stevens more specifically on the nature of Keaton’s mystery:

“In trying to understand not just the work and life of Buster Keaton but the world into which he was born—to understand him through that world, and that world through him—I keep returning to the now-insoluble riddle of his persona as a child performer. Why is it that trying to reconstruct the particular content and audience appeal of the act he and Joe built together over the course of Buster’s seventeen years as a juvenile slapstick prodigy feels like a meaningful pursuit, half a century after Keaton’s death and not many fewer decades since the youngest person to have witnessed one of those ephemeral sketches must also have passed from the earth?

“Some part of it must be simply regret at having missed the chance to see the child Buster in performance: the melancholy of temporally bound existence, of having to occupy a fixed place in history and experience all of the past only through the fragmentary records left by others. I want to witness Buster, Joe, and Myra (and, for the brief period when they were less-than-successfully brought into the act, Harry and Louise) doing whatever their Keaton thing was onstage—not via the archive-augmented time machine of imagination but live and in person, preferably without any foreknowledge of who that airborne kid would grow up to be. I want to know what their act looked, sounded, and moved like as they amused and startled jostling, sweaty crowds in a gaslit (or, by the Three Keatons’ second decade on the boards, likely electricity-fueled) theater.”

The two books can be shuffled into each other like a deck of cards, and read in tandem create delicious resonances, and celebrate one of the cinemas greatest directors, indeed someone who helped create cinema.

- KBOO